Welcome to Rare Candy #3

Happy New Year and welcome back to another edition of Rare Candy.

Apologies for not releasing a newsletter in December 2022. Unfortunately I had a family member pass away early December and had to fly overseas for a few weeks. I had promised a bottle (or two!) of champagne for the 'team' who had the most subscribers, but it made sense at the time given it was the festive season. I might hold off on that until Easter or when it makes sense to celebrate (I know it's a cop out).

If you’re new here, Rare Candy is a newsletter that aims to provide deep and insightful analysis on venture capital. You’ll want to read my first piece here and my second piece before this one.

If you’re interested in collaborating, please reach out to me here. I’d love to share some ideas and see how we can work together.

Summary

Smaller venture funds (<$100m) are likely to return their fund with a median-size SaaS exit.

To return larger funds, patient capital is required, and funds should consider long-term valuation creation post-IPO.

Cross-over funds (private and public market funds) are becoming common and may be a potential model for 'patient capital' in the future.

I love investing. I’m addicted. I love ‘levelling up’ and learning about interesting asset classes like vinyls, whiskey, Pokemon cards and more. That's why I've been reading Alts. Stefan and Wyatt write deep analysis on alternative assets and you get to reap the rewards.

Join 50,000+ others and see what you’ve been missing.

Introduction

I read this article over the summer break (a riveting way to spend my holidays, I know). It makes a bold assertion that a venture fund should be no larger than 1-1.5x the average exit value in a domain or sector. This was from 2011, and I wanted to understand:

How large do exits need to be if fund size keeps increasing?

Do those exits exist?

Returning a Venture Fund

The threshold for a ‘good’ fund is to return 2-3x cash-on-cash or more. Top performing funds can return substantially more. For example, Union Square Ventures has generated returns ranging from 3.9x cash-on-cash to 7.3x cash-on-cash.

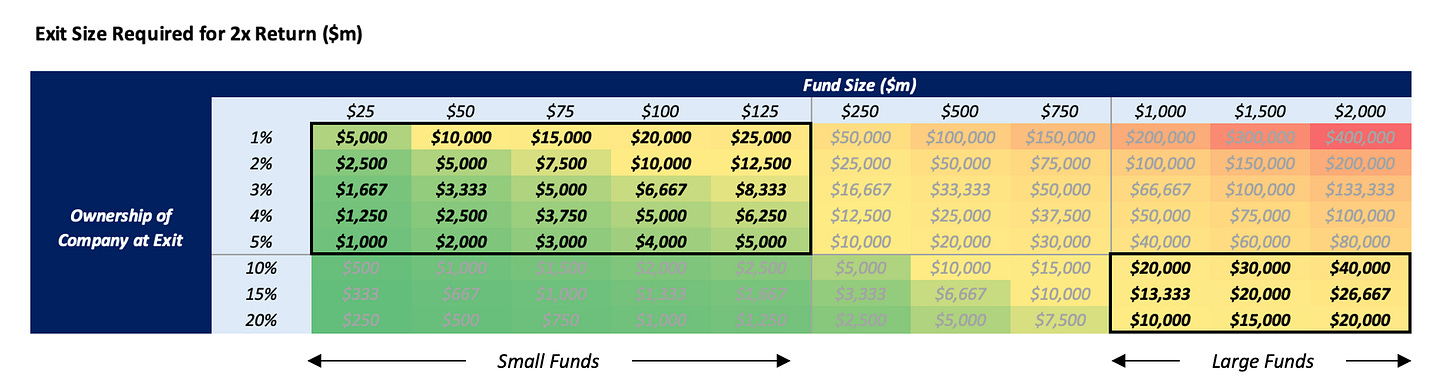

Working backwards from 3x cash-on-cash as a baseline, you can solve for the exit value of one company that would achieve this return, assuming an ownership stake and a fund size:

We know that returns are power law distributed. Therefore if you assume that only one company is successful at returning capital then:

For a small fund to return 3x, it would need an exit valuation between $1.5b - $37bn. I've assumed that their ownership stake is between 1-5% (shows you how sensitive fund returns are to ownership). This is relatively small, but smaller funds don't have the capital to continuously exercise pro-rata (or lead future rounds in their successful portfolio companies), which means they are likely to be diluted down to lower ownership stakes.

Additionally, it could be argued that in a competitive venture ecosystem, smaller funds may be 'competed out’ of leading rounds and can only take smaller ownership stakes to fill remaining allocation.

On the other hand, for a large fund to return 3x, it would need an exit valuation between $15 billion and $60 billion. I've assumed that a larger fund can continuously exercise pro-rata and lead future rounds in their portfolio companies, meaning it's likely they'll hold 10-20% of a company.

It's important to note that portfolio companies aren't ‘return or nothing’. There are mid-range exits, secondaries, and downside protection through preference stacks, etc. which means funds do have a spread of exits rather than 'all or nothing.'

Even if you assume a 2x return (cash-on-cash) because the other 1x is covered through other means, larger funds are still looking for outcomes of over $10b.

By working backwards, we have determined the scale of exit required to return a venture fund.

However, do exits of that scale exist?

The Power Law Within the Power Law

Large funds require at least a $10b valuation at exit (~$14bn AUD).

However, there are currently over 1,200 unicorns, and only 54 (~5%) of these are valued at over $10 billion USD (and 97 at $10bn AUD). Furthermore, only one of these companies is Australian (Canva). This means the probability of a large portfolio company is very low, these are the outliers of outliers.

For smaller funds, they need to be at least unicorn status at exit, depending on their ownership.

The median unicorn valuation right now is $1.6b USD (realistically lower because the data is from October ‘22 but let’s roll with this as this is readily available data). That’s $2.2b AUD.

On this valuation, this would return 2x of a fund less than $50m, assuming they owned ~4-5% of the company (very probable to own this stake if you led one of their first rounds of financing).

This is pretty interesting to think about!

Unicorn companies are already in the top 1% of their class and even for small venture fund, you would need a median company within that top 1% cohort to return 2x of the fund. No wonder many venture funds don’t succeed!

I want to illustrate an example of how this plays out. Assume that private market and public valuation multiples are at parity at later stages. If you had a $100m venture fund, in order to return 3x cash-on-cash, you would need:

Between three to five exits of a company valued at $2-3b (assuming lower levels of ownership). HARD. Remember, the median unicorn valuation right now is $2.2b AUD and now you need at least three of these. Go look at the portfolio of any venture fund and tell me how many have three unicorns or more within a specific fund.

One or two exits of a company valued at $5b. In Australia, only Canva has hit this milestone. And don’t forget you have to compete against the Blackbirds, the AirTrees and the Square Pegs of the world, as well as the highly differentiated funds like AfterWork and EVP to win deals or get allocation. DOUBLE HARD.

One exit for a company valued at $10b or more depending on ownership. Venture is already an asset class of outliers and now you’re looking for the most extreme of outliers. Remember, right now there are only 54 companies with a valuation of $10b USD or more, putting them in the top 5% of all unicorns. TRIPLE HARD!

I’m using unicorn valuations as a proxy for exit valuations, given that multiples should regress to public market multiples when they approach this size and scale. At the moment, very few private companies could return even 2x of a $1b fund, let alone the $5b growth fund that a16z raised in 2022 (part of a cohort of funds totalling $9b).

IPOs and M&A

Portfolio exits occur at all sorts of valuations and they often differ from their last private market valuation.

IPOs would need to be at a higher valuation than their last private market financing in order to return capital to investors at that stage. For example, Uber’s last financing round was at a valuation of $76b and it went public at a valuation of $82b.

Corporate development teams are likely to overpay for large acquisitions as a defensive mechanism to maintain incumbency. Figma was valued by Adobe at $20b at the time of the acquisition offer - twice the valuation of the company at its last financing round.

Knowing there’s variability between last funding round valuations and exit valuations, we can look at recent data to tell us what these valuations look like at IPO (acquisitions are harder to look at because there are fewer large scale benchmarks!).

If you zoom in on this beautiful bar chart, you’ll see that enterprise SaaS has a median IPO valuation of $2.8b (~$4b AUD). At this valuation, you could return 3x your $100m fund if you can own around 7.5% of a company that made it to this size and scale. This seems pretty reasonable assuming you start at around 20% ownership when you first invest. However, this is US centric data.

The Australian perspective is harder to infer given the limited data available and immaturity of technology listing on the ASX but as a single data point, Siteminder went public in late 2021 at a market cap of $1.36b.

To summarise, if you want to return a small-ish VC fund of $100m, you’d just need a median US-enterprise SaaS exit or three Siteminder-level Australian IPOs.

As fund size increases, funds can’t settle for a median sized enterprise SaaS exit, which means they can’t just be investing in SaaS.

If you have a $500m-$1b fund, it would be nearly impossible to return a 3x the fund on SaaS exits alone.

If the median SaaS IPO was valued at $4b AUD (~$2.8b USD), you’d need three or four to return 3x the fund (assuming 10-20% ownership). There’s not four startups of that scale in Australia at the moment!

One of the largest cloud/software IPOs was Snowflake (~$34b) and even Snowflake pales in comparison to some of these consumer companies like Meta and Uber.

Given the scarcity of these exits, investors may have to become post IPO owners of companies if they’re managing larger amounts of capital.

Long Term Capital and Public Markets

There are 580+ US listed companies that currently have a market cap of >$10b. This number would be much larger if you include other regions. Some of these were once venture backed companies. That’s 10x the amount of private market companies valued at the same level.

Some of these companies have created this value long after they went public. The ‘legacy’ examples of this are Microsoft, Apple and Alphabet but you can look at more recent examples including Atlassian, Salesforce, Uber and Airbnb.

Throughout this edition, I’ve assumed that funds divest at IPO. This is a false assumption. Some funds continue to hold their ownership in companies long after their IPO.

Some funds already do consider themselves as ‘long term capital’, rather than venture capital.

If you’re looking for founders who can create long term and sustainable value and truly believe in those founders to do this, it doesn’t make sense to divest at IPO (or maybe just a little so you can return capital and raise another fund).

They’ve already built and shown they can create value and build an enduring company;

There’s greater availability of capital in public markets. Companies can utilise this capital and invest in greater volumes to continuously innovate, build new products, acquire adjacent players and expand across value chains;

At times, the discipline and rigour of public markets and public market participants can act as a forcing function to ensure long term value creation (Elon Musk, activist investors etc).

In 2015, Altimeter Capital led Snowflake’s Series C at $2.29 per share and continued to invest in every round after. Unlike many of the earlier investors in Snowflake, Altimeter still remains of one of the largest investors in the company and the Partner who led the deal within Altimeter, Brad Gerstner believes Snowflake will continue to create long-term value.

Imagine if you had sold at IPO (which was priced at $120) only to see multiple expansion driving the share price to $390+. That is more than a 3x return, which would put your fund in top 5% of venture funds. I’ve outlined above at the difficulty in returning 3x in the asset class, but here’s one in the public markets! But imagine if you were Sutter Hill, they invested in Snowflake’s Seed and Series A. That’s an incredible return if they held past IPO.

Of course, this situation was a unique outlier given the extreme multiple expansion that occurred in the public markets between 2020 and 2021. You can look at the share price history and the evolution of companies like Adobe, Alphabet, Microsoft and Amazon as comparable companies who have existed for decades. These companies have shown the ability to create value and reinvent themselves in public markets.

The power law isn’t unique to venture and does manifest in public markets and this is where the outliers of outliers emerge. And larger funds like Altimeter and Tiger know this, which is why they’ve structured themselves as cross-over funds.

In time, I think we’ll see more cross-over funds emerge as patient capital and play earlier, which will paint a gloss over their ‘hedge fund’ status. These funds have ‘proper villains’ who have strong finance and investment backgrounds which, when applied correctly, can translate to early stage diligence.

In my first job, I spent months crawling through S1s and 10Ks to benchmark SaaS company margins and OPEX for a project I was working on as a consultant. It would be a lie to say looking at annual reports of mature technology companies isn’t useful to my job right now working with early stage startups.

There is definitely a challenge for venture funds who become cross-over funds in building this capability internally!

Concluding Thoughts and What’s Next

I concede that the immaturity of the technology ecosystem in Australia plays a role in this as well. Do I believe in the next 10 years that we’d see more unicorns and greater value creation or do I believe that it will remain at these volumes (or lower)? Absolutely, I believe that there’s more value to be created and that we'll see many more Australia companies reach >$10bn and more.

I want to meet some LPs and learn how they think about venture allocation. There’s lots of VC / startup hang outs, but where do LPs hang out?

I’m going to do some cold outreach, but if you’re an LP in a venture fund, please reach out. I promise I won’t ask for your money. I’d love to write an article about venture allocation from the perspective of LPs.

Pop Culture, Life, Reading and More

I won my Fantasy Football (NFL) league, Superbowl is coming up and would love to organise a watch party if anyone is interested!

The day this drops, ‘The Last of Us’ by HBO will have been released. Worth a watch, even if you’ve never played the game (the game is unreal!).

I’ve started reading ‘The World in a Grain: The Story of Sand and How it Transformed Civilisation’ after a friend recommended it. It’s excellent so far!

Mark, a mentor of mine and fellow VC has started a newsletter. He’s a genius so I would recommend it.

We’ve (Astral Ventures) built a VC leaderboard that lets AU/NZ founder rank their VCs. Would love for you to share it!