Venture Portfolio Strategy and Probability

Nerding out on probability weighted success in venture capital

Welcome to Rare Candy #2

I’m humbled and grateful for the support I’ve received for Rare Candy since launching last month. If you’re new here, Rare Candy is a newsletter that aims to provide deep and insightful analysis on venture capital.

Thank you to the 300+ subscribers who have joined me on this journey. The majority of which are investors from VC and startups. I know you’re a competitive bunch, so each edition I’m going to post a ‘podium’ of my top VC or startup supporters.

Here’s the current leader board:

To be completely transparent, this is how I’m assessing the podium.

I’ll send two bottles of champagne to the fund or company who makes it to the #1 spot next month. If AirTree takes the top spot, I’ll even send it via Milkrun.

If you’re interested in collaborating, please reach out to me here. I’d love to share some ideas and see how we can work together.

Summary

Key Insights

Just here for the takeaway? Here is what you need to know:

Portfolio strategy and construction differs between funds - all these funds are playing the Power Law game but some play it very differently.

If you can’t source, assess and win the absolute best founders maybe ‘spray and pray’ is the right decision - If you can’t pick the right players to score a goal, getting as many players on the field as possible may also be a winning strategy.

I love investing. I’m addicted. I love ‘leveling up’ and learning about interesting asset classes like vinyls, whiskey, Pokemon cards and more.

That's why I've been reading Alts. Stefan and Wyatt write deep analysis on alternative assets and you get to reap the rewards.

Join 50,000 others and see what you’ve been missing.

Primer on the Power Law

The startup ecosystem thrives beacuse of a rule called The Power Law which defines the return profile of early stage VC investments. Simply put, given a incredible large enough cohort of startups, only a handful of of those will product expotential returns. Returns which are greater than the returns of all other companies combined.

This is nicely summarised by Peter Thiel in his book Zero to One:

‘… the biggest secret in venture capital is that the best investment in a successful fund equals or outperforms the entire rest of the fund combined.

If you believe this statement, this means success can be determined on whether a startup can return a fund, or multiples of a fund.

And if you’re a VC and you’ve found a company that has the potential to do that, they want to optimise ownership in that company in order to maximise their return (in reality there’s other factors including portfolio concentration and so forth but let’s keep it simple).

This makes VC sound really easy when you reduce it to this process:

Unfortunately, we know (from the Power Law) that only a few companies can generate outsized returns. We also know that ownership of these companies is a zero-sum game (the more ownership you own, the less anyone else owns). This means VCs need to find and invest in the best founders and companies and these companies need to create enough value such that the VC’s stake in the company is worth the original value of the fund, or more.

VC Decision Making and Shot Selection

This is where we all get to nerd out.

Warning: this will get a tiny bit technical. Here’s a quick primer to help frame the technical aspects that follow below.

The purpose of venture capital is to score a goal (a return).

Imagine if every player had a ball, then there are two ways to do this:

You get as many players onto your team as possible. The more players and balls on the field, the more goal attempts.

You pick only the best players for the team. This means you have a smaller team but better players might maximise the probability of a goal.

Technically, you could do both (i.e. aggregate all the best players) but this is hard to do given some players might choose to go to other teams (other funds).

Now for the technical part.

Venture capital could be described an extensive-form game depicted as a game tree. For those unfamiliar with extensive form games, it’s a sequential game that where the players makes a set of probability based decisions (with complete or incomplete information), with an inevitable pay-off at the end.

Put simply:

Each turn, a player (VC fund) will make a decision to invest in a company on the basis of complete or incomplete information (diligence)

At the end of the turn, the company will be successful or unsuccessful (determined by probability)

And then the players can choose to invest again (follow on investment)

This repeats until there’s a payoff (liquidity event)

We’re able to depict this here using a variation of a game tree that I’ve adapted from Ewens et al. (2017):

This game tree outlines the return ($V) for an investor on a two-stage investment process. The aim of venture capital is to maximise $V.

At the first step, investors have to source deals and make a decision whether to invest or not invest. If an investor chooses not to invest in the company, they keep $X and $Y but don't get the returns. If they choose to invest, then $X is invested into the startup, reducing their total pool of funds

The startup then uses that money and runs experiments within their business to validate their hypothesis. After they’ve taken this money, the startup has two probabilistic outcomes of their experiementation (the probability of success is P1, and the probability of failure is 1-P1. The assumption here is after their first experiment, if the founders, choose then to ask for more money

Based on the outcome (success or failure), the investor can then choose to invest again and give the founders more money. In which case the startup has more cash to run experiments and further validate their additional hypotheses or the investor can keep $Y (the money used for follow on investments).

With a follow-on investment, there’s conditional success:

PS - the probability of success after the first success, and

PF - the probability of success after the first failure.

We can assume that PS > PF (this means two successful outcomes in a row is likely to lead to a greater probability of $V than one failure and then one success). Ultimately, success is a function of the probability that a startup can be successful across multiple stages of their business (success = validating a hypothesis at each stage of the company).

This means that the probability of $V (the probability of a return) can be mathematically described as:

For those who aren’t mathematically inclined, this means the probability of a return (success) is the sum of both avenues for success (probability two successes in a row (P1 x PS) plus the probability of a failure and a success (1-P1 x PF).

If you want to take it even further, that means the expected return (denoted as E(V)) is just the probability of a return, multiplied by the magnitude of a return:

Recalling that VCs want to maximise the value of the eventual payoff $V this means they have two ways to do this (given that PS > PF):

Maximise the magnitude of $V - This is why VCs are obsessed with founder ambition and vision. Naturally, the founders with the grandest ambitions have the most room to run and when there’s lots of room the run, the value of $V can get very large, and large enough for exponential returns such that the Power Law comes into play. Some investors think about this value ($V) as TAM, but if you believe in a founder’s ability to create value, particularly in new markets they have created, then the focus should be on ambition and aspiration rather than TAM. This means trying to quantifying $E(V) (i.e. the total potential return) at the early stage is more of an abstract exercise

Maximise the probability value of P(V) - choosing the subset of founders with the greatest probability of success. Obviously it goes without saying that these founders also need to have large potential $V values such that you can realise venture scale returns, but really the optimisation here is founders with the highest possible P1 values, or PS or PF values. This means in order to maximise P(V), investors should invest in founders that will have either (or both):

The highest probability of success at the first stage of experimentation; or

Incredible resilience - founders who can maximise the probability of success after failure

Unfortunately for all the VCs reading this, there’s not a magic, endless supply of ambitious, resilient and high probability founders in market. And even if there was, trying to assess and quantify these values is incredibly difficult given the broad and variable that which founders come from. Assessment of success is also rife with bias adding to the difficulty, and there are VCs who admittedly have no idea how to make assessments in particular domains, which restricts the pool of high probability founders they can draw upon.

Now here lies the two diverging schools of thought in VC:

VCs who believe that P1 (and subsequently PS and PF) can be quantified accurately and maximised and only invest in founders and companies they believe have maximum P1. Conventionally, you could call this ‘high conviction’ investing. These VCs optimise for ownership in these companies at first cheque and continue to follow on in subsequent rounds.

VCs who have a P1 benchmark threshold and invest in any founder or company who meets the minimum threshold P1 value. Inverse to the above, this is optionality investing and if you take this to the extreme at lower P1 values, this could be described colloquially as ‘spray and pray’ investing. These VCs will write smaller cheques intially and then take larger, more meaningful stakes in later rounds or in the case of ‘spray and pray', not follow on at all and simply invest only once in a company (at the earliest cheque, entry points at low so you can still achieve sizeable ownership)

Sourcing the best companies and most ambitious founders is a difficult exercise and even if you can source these founders, given there’s a finite amount of these companies and finite ownership of these companies, it makes venture competitive for top companies, which then increases the entry point for investments and potentially eroding away return multiples.

You can effectively distill venture capital as a function of several things:

VC Sourcing Efficiency - finding P1 founders. These are the founders who have the highest probability; and

VC Assessment Ability - assessing that they are truly P1 startups and subsequently assessing for PS and PF; and

VC Value Add - the ability of support and infuence the success of a startup (i.e. PS/PF and subsequent probability rounds) such that you can increase the overall probability of P($V). No jokes and cliches here, this is actually a real thing that can influence the success of a company.

Venture Probability in the US

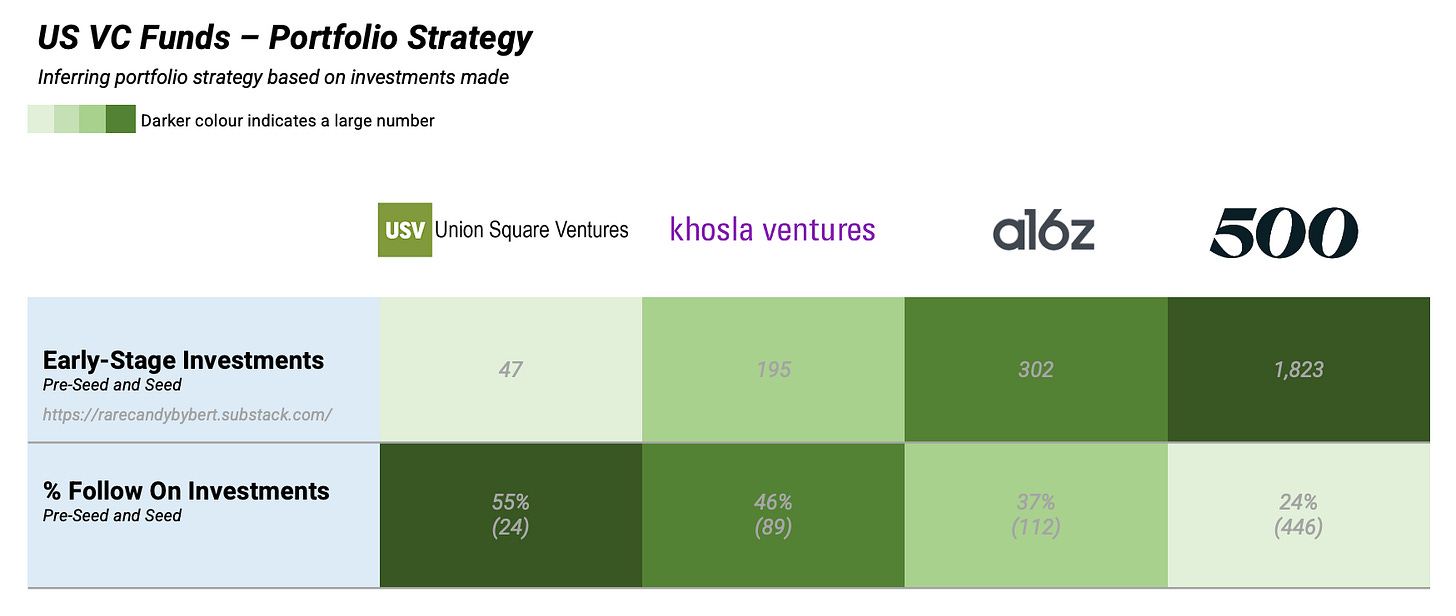

I’ve chosen a selection of US based VC funds to illustrate differences in early stage VC portfolio strategy. These funds to invest across a range of stages but I’ve only accounted for their early stage investments (Pre-Seed and Seed) where arguably the probability of success at the first experiment (P1) is very low.

My starting point is that I’m assuming that a VC will ‘follow on’ in investment regardless if the initial experiment was a success or not. This means they believe the founders can still generate a return from subsequent, successful experiments.

The inverse to this is VCs who will only invest in a ‘follow on’ round if the initial experiment was successful. The implication here (flicking back to the logic tree above) is that a VC will not invest if an initial experiment fails because the opportunity cost outweighs PF (the probability of success after failure).

In truth, there’s actually a lot of reasons why a VC doesn’t follow on. Sometimes they’ve run out of funds or don’t have the funds to deploy at later stages. Maybe their LP mandate has restricted them from investing in later rounds. But if you believe that VC’s want to optimise for ownership in the top performing companies, it’s more than likely they will continue to invest in their ‘winners’ at least one more time after their first investment.

Let’s dive into this table.

Union Square Ventures is one of the best performing VC funds in the world.

USV has a small and highly concentrated portfolio (they mention their 2016 fund aimed to invest in 20-23 companies), which means they invest a larger proportion of their fund into each company. This outlines that USV is a ‘high conviction’ investor

This shines through because a large number of their investments receive follow on investments, meaning they had strong belief in the initial investment such that they are going to continue to support the founder and invest to maintain (or grow) their stake, regardless of whether the first experiment was a success or not

You could also assume the initial experiment failed and that USV only invested in the successful companies. But given their high follow on percentage (>50%), this means USV believes they have high skill at picking the right founders to back (P1 founders)

USV has had 48 exits and a number of their portfolio companies have graduated to the public markets including Twilio, Cloudflare, Etsy and Twitter (none of these were Pre-Seed or Seed investments however!). This puts their exit rate at around 25% across their entire portfolio which is an impressive goal rate

The complete inverse of USV is 500 Global. Their website boasts they have invested in over 2,600 companies. I’ve got data for 2,200 and of that list, 1,823 of these companies where invested for the first time at Pre-Seed or Seed.

500 Global could be described as an optionality investor with a portfolio of early stage companies of this size. They invest all around the world in a broad set of domains and verticals so it’s likely that they have a P1 threshold and they’re optimising for shots on goal instead of trying to build the absolute best team

The majority of their investments don’t receive follow on investments - only a quarter of their investments receive follow on. There’s some nuance here but I don’t necessarily think it’s for lack of funds. For example, they invested in African unicorn ChipperCash at their Seed round and continued to invest until their Series C (their latest round)

I’m sensing that 500 Global invests a small amount initially (smaller $X) and then follows on in their successful companies (larger $Y). And this strategy is actually working for them! They boast that their portfolio has 49 unicorns and 150+ companies with a valuation greater than $100m

This is almost like a development squad. By choosing to invest in a large amount of players, they get access to information that helps them make future decisions, and then they can create a new team of players who are more likely to score goals (follow on investments)

As a side note - if you’re a high conviction fund, consider seeding an earlier stage with a larger and more diversified portfolio for access to companies and information without impact to your own brand

These two funds showcase how the game-tree above plays out in reality. If you’re a VC who can assess for P1 at incredibly high accuracy and fidelity, then it’s worth maintaining a small, concentrated portfolio. This also means you can work closely with founders to influence PS or PF values and improving the probability of a return.

If you’re VC who would prefer to instead maintain a highly diversified and large portfolio, you should set a benchmark for P1 and write optionality cheques that give you the ability to invest again for greater ownership if the initial experiment was successful. This would lead to much larger portfolios, reducing the time you can spend with founders, but gives you more time to source new founders and deploying at faster rates.

Some VCs do both and perhaps Khosla and a16z are two examples of this given they sit between the spectrum of USV and 500 Global. My personal take is that it can be difficult to execute on this unless you have the right infrastructure internally to support a growing portfolio, otherwise you risk not being able to support founders. And this has ramifications on your ability to win future deals if you’re unable to provide the support to founders you’ve otherwise said you can. There is a very real trade-off between fund portfolio size and success and only the best VCs can navigate this trade-off effectively.

This is another reason why it could be worth seeding other funds as you won’t have to make that trade-off.

Final Thoughts on VC Decision Making

This was actually very interesting to write and think about. Playing the thought experiment, if I was running my own fund:

Would I be a high conviction investor with a highly concentrated portfolio or would I run an optionality fund with a much larger portfolio?

There’s overlays to this as well. With a smaller fund (<$20m), it might be difficult to execute a portfolio strategy that requires me to invest in 50-100 companies. There’s the funnel overlay - if only 1% of companies are VC backable, then you would need to see 10,000 companies to back 100. This would require someone to be across multiple domains and verticals and the market in Australia may not be large enough for that.

Additional Reading

I highly recommend these two papers both of which I have used extensively for this article:

We Have Met the Enemy…and He is Us from the Kauffman Foundation

Predicting Success in Early Stage Venture Capital by Hans Jacques Lindahl Falck

What’s Next?

I have something incredibly spicy but I’ll only release when this hits 1,000 subscribers. If you want some real and deep inside baseball, better get sharing.

I’d love to hear from you if there was something that reasonated in this article or if you have feedback for me. Shoot me a message, DM me on Twitter, add me on Linkedin, or even UberEats me some pizza (rip Deliveroo).

If you’re interested in collaborating, please reach out to me here.

Pop Culture, Dating and More

As promised:

I was in Canberra last weekend for Dad’s birthday. Every time I’m back in Canberra, I can’t help notice the incremental things that make it even cooler. There’s some pretty impressive founders in Canberra too, maybe it’s an untapped bastion of alpha

I went on a first date this week - seemed promising with a second one lined up! More on this later!

I’m surprised Pokemon hasn’t gotten into NFTs. Seems like a great use case. You could make them interoperable across games and there’s rarity in Pokemon so naturally lends itself to exclusivitiy. And people are already obsessed with catching them all.